When a brand-name drug company holds a patent, it gets a monopoly on selling that drug for years-sometimes over a decade. But what happens when a generic version wants to hit the market before that patent expires? That’s where Paragraph IV certification comes in. It’s not a loophole. It’s a legal tool built into U.S. drug law to force patent disputes into court before generics even start selling. And it’s how billions in savings get passed on to patients.

What Exactly Is a Paragraph IV Certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a formal statement made by a generic drug company when it files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA. In this statement, the generic maker claims that one or more patents listed for the brand drug are either invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed by making or selling the generic version.

This isn’t just a guess. The law requires the generic company to lay out the factual and legal reasoning behind this claim. It’s not enough to say, “We think this patent is weak.” You have to show why. That could mean proving the patent covers something already known, or that the generic drug works differently enough to avoid infringement.

The whole system comes from the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Before that, generic companies had to wait until every patent expired-even if those patents were questionable. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It gave generics a legal pathway to challenge patents head-on, but with rules. The result? More competition, lower prices, and a structured way to resolve disputes before drugs hit shelves.

How It Works: The Step-by-Step Process

Here’s how a Paragraph IV challenge plays out in real life:

- File the ANDA: The generic company submits its application to the FDA, including the Paragraph IV certification and the detailed legal basis for challenging the patent.

- Send the notice letter: Within 20 days, the generic company must mail a formal notice to the brand-name drug maker and patent holder. This letter isn’t a friendly heads-up-it’s a legal trigger. It says: “We’re challenging your patent. Be ready.”

- Brand company sues: If the brand company wants to block the generic, it has 45 days to file a patent infringement lawsuit. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months-or until a court rules otherwise. That’s called a “30-month stay.”

- Litigation begins: This is where things get expensive. Lawsuits can drag on for years. The median cost? Around $12.7 million per case. But if the generic wins, they get the prize: 180 days of exclusive market rights.

- First to file wins exclusivity: Only the first company to submit a complete ANDA with a Paragraph IV certification qualifies for the 180-day exclusivity. If someone else files after them, they can’t sell until that exclusivity period ends-even if they also win their case.

It’s a high-risk, high-reward game. Lose the lawsuit? You’re stuck waiting until the patent expires. Win? You get a free pass to be the only generic on the market for half a year.

Why Do Generic Companies Take the Risk?

The answer is simple: money. The 180-day exclusivity period is worth millions-if not billions-on blockbuster drugs.

Take Mylan’s challenge of Gilead’s patent on tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. The patent was set to expire in 2022. Mylan challenged it in 2017. After a long legal battle, they won. Their generic hit the market 27 months early. During their 180-day exclusivity window, they captured nearly all the sales. That’s tens of millions in revenue, all before other generics could even apply.

Apotex did something similar with GlaxoSmithKline’s Paxil. After winning their Paragraph IV challenge, they made over $1.2 billion during their exclusivity period.

But here’s the catch: you have to be first. If you’re second, third, or fifth to file, you get nothing. That’s why companies rush to submit their applications the moment they’re ready. The race isn’t just about science-it’s about timing, paperwork, and legal strategy.

The Other Three Certification Types (And Why They’re Less Common)

Paragraph IV isn’t the only option. There are three others, and they’re far less aggressive:

- Paragraph I: “This drug isn’t patented.” Only about 5% of ANDAs use this. It’s rare because most brand drugs have at least one patent.

- Paragraph II: “The patent will expire soon.” About 15% of applications use this. It’s safe-no lawsuit risk. But you have to wait until the patent ends.

- Paragraph III: “We won’t sell until the patent expires.” Around 20% of applications go this route. It’s the safest path, but it gives up any chance of early entry.

Paragraph IV is the outlier. It’s used in 60-70% of ANDAs filed for drugs with active patents. Why? Because the payoff is huge. The risk is high, but the reward? A six-month monopoly on a $2 billion drug can be worth $500 million.

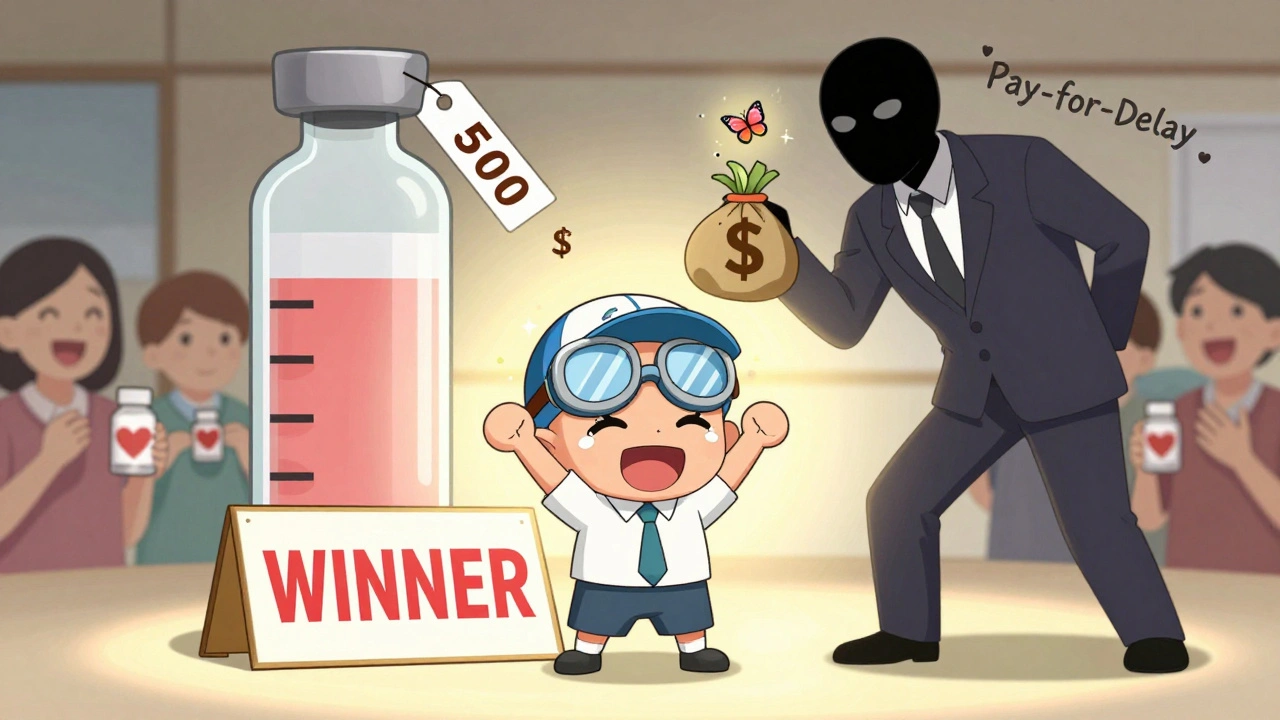

The Dark Side: Pay-for-Delay and Patent Thickets

It’s not all fair play. The system has been abused.

“Pay-for-delay” deals happen when a brand company pays a generic maker to delay entering the market. In exchange for cash, the generic company agrees to hold off on selling-even after winning their legal challenge. The FTC called these deals “controversial” and found 197 of them between 1999 and 2009. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled these deals could be illegal under antitrust law. But they still happen.

Another problem? Patent thickets. Brand companies file dozens of patents on the same drug-covering everything from pill shape to manufacturing process. Even if one patent is weak, another might hold up. Generic companies have to fight them all. According to a 2022 survey, 63% of generic manufacturers say patent thickets have made challenges harder since 2018.

And then there’s the “authorized generic” trick. Sometimes, the brand company launches its own generic version during the 180-day exclusivity window. That floods the market and cuts the first filer’s profits. The FTC has challenged this practice, but it’s still legal.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The rules are slowly shifting. In 2023, the Supreme Court’s decision in Amgen v. Sanofi made it harder to invalidate patents by requiring that the patent’s claims be fully “enabled”-meaning the patent must clearly teach how to make and use the invention across its entire scope. That’s a big deal for biologics and complex drugs.

The FDA also updated its Orange Book rules in 2024 to reduce misleading or overly broad patent listings. That should help cut down on patent thickets.

Meanwhile, more generic companies are combining Paragraph IV challenges with Inter Partes Review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPRs are cheaper and faster than court cases. If you can knock out a patent there, you weaken the brand’s case in court.

And the numbers don’t lie: 90% of top-selling brand drugs face at least one Paragraph IV challenge. The FDA estimates these challenges have saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.7 trillion since 1984. That’s not just corporate profit-it’s lower prices for insulin, heart meds, antidepressants, and cancer drugs.

Who’s Winning? Who’s Losing?

The top five generic manufacturers-Teva, Viatris, Sandoz, Hikma, and Amneal-control nearly 60% of all Paragraph IV filings. They have the legal teams, the resources, and the patience to fight five-year lawsuits.

But small players still win. In 2021, a little-known company called Zydus won a Paragraph IV case against a major brand’s patent on a cholesterol drug. Their generic launched early, and they captured 80% of the market during their exclusivity window.

On the flip side, Teva lost its 180-day exclusivity in 2017 because they didn’t get FDA approval within 30 months of filing their challenge. They thought they were safe. They weren’t. Another generic rushed in the same day. Teva got nothing.

That’s the lesson: even if you win in court, you can still lose in the paperwork.

Final Takeaway: A System Built to Force Competition

Paragraph IV certification isn’t about breaking the law. It’s about using the law to break monopolies. It’s a carefully designed tool that lets generics push back against weak patents, rewards the first mover, and ultimately drives down drug prices.

It’s messy. It’s expensive. It’s full of legal traps. But without it, most generic drugs wouldn’t enter the market until patents expire-even if those patents shouldn’t have been granted in the first place.

Every time a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification, they’re not just trying to make money. They’re trying to make healthcare more affordable for millions of people.

What happens if a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification but doesn’t win the lawsuit?

If the brand company sues and wins, the FDA blocks the generic drug from approval until the patent expires. The generic company loses its chance at 180-day exclusivity and must wait like everyone else. They also pay millions in legal fees with no return.

Can a generic company challenge multiple patents in one Paragraph IV filing?

Yes. A single ANDA can include Paragraph IV certifications for multiple patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. But each challenge must have its own detailed legal basis. Filing too many weak challenges can backfire-brand companies may use it to argue the generic is acting in bad faith.

Why is the 180-day exclusivity period so valuable?

During those 180 days, no other generic can sell the same drug-even if they’ve already gotten FDA approval. That means the first filer captures nearly all the market share. On a $2 billion drug, that can mean $500 million in revenue before competitors even enter.

Can the FDA reject a Paragraph IV certification?

Yes. The FDA doesn’t judge whether the patent is valid-they only check if the certification meets the legal requirements. If the notice letter lacks a detailed factual and legal basis, or if it’s not sent within 20 days, the application can be rejected. About 12% of Paragraph IV filings in 2021-2022 were rejected for these reasons.

What’s the difference between a Paragraph IV challenge and an IPR?

A Paragraph IV challenge happens in federal court as part of the ANDA process and can lead to 180-day exclusivity. An Inter Partes Review (IPR) is a faster, cheaper proceeding at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) that only challenges patent validity. Many generic companies now use IPRs to weaken patents before filing a Paragraph IV challenge, making their court case stronger.

Are Paragraph IV challenges only for pills?

No. While most Paragraph IV filings are for oral drugs, they’re increasingly used for complex generics like inhalers, injectables, and topical creams. The FDA expects a 78% increase in these types of challenges between 2023 and 2028 as more complex drugs lose patent protection.

Comments

So let me get this straight - a company spends $12 million in legal fees just to be the first to sell a generic pill, and if they win, they get to make half a billion dollars? Sounds less like healthcare reform and more like Wall Street with a stethoscope. 🤡

This is actually beautiful. In India, we know how expensive medicines can be. This system, even with all its flaws, gives hope to people who can’t afford brand drugs. Let’s not forget - behind every generic pill is someone who couldn’t pay for the original.

Keep fighting the good fight, even if it’s messy.

One must interrogate the ontological underpinnings of pharmaceutical capitalism before lauding Paragraph IV as some kind of populist triumph. The 180-day exclusivity regime merely reconfigures monopoly into a temporally bounded oligopoly - a Hegelian dialectic of exploitation, where the proletariat are granted fleeting access to the commodity they were previously denied, only to be re-subjugated by the next patent thicket.

And yet, one cannot help but admire the tragicomic theater of it all: corporate titans clashing in court over the molecular geometry of a pill.

It is morally indefensible that a corporation can profit from a legal loophole that allows it to exploit the suffering of patients. The 180-day exclusivity period is not a reward - it is a perverse incentive to prolong pharmaceutical greed. The fact that this system is celebrated as ‘innovation’ is proof of our collective moral decay.

These companies are not heroes. They are predators with law degrees.

Let me be perfectly clear: if you think this system is fair, you haven’t read the fine print. The ‘first to file’ rule isn’t a meritocracy - it’s a lottery rigged by billion-dollar legal teams. Small companies don’t stand a chance. The FDA’s rejection rate for improperly filed Paragraph IVs? 12%. That’s not a bureaucratic hiccup - that’s a gatekeeping mechanism disguised as procedure.

And don’t even get me started on the authorized generics. That’s not competition. That’s corporate sabotage dressed up as capitalism.

The whole thing is a scam and everyone knows it

Wait so if you win you get 180 days of monopoly... but if you lose you lose millions?? 😳

That’s like betting your house on a coin flip and the prize is a golden toilet.

Also - IPRs are kinda wild tbh. Patent office vs court? I’d take the PTAB any day. 🤖⚖️

The structural dynamics of Paragraph IV certification reveal a deeply ambivalent equilibrium within the U.S. pharmaceutical regulatory framework. While it ostensibly promotes competition and reduces consumer costs, the mechanism simultaneously incentivizes strategic litigation over genuine innovation, thereby entrenching a system wherein legal acumen supersedes therapeutic utility. The 180-day exclusivity window, though economically rational from a corporate perspective, functions as a distortionary subsidy that undermines the very notion of equitable market access.

Furthermore, the increasing integration of Inter Partes Review with ANDA filings suggests a procedural convergence that may ultimately erode the jurisdictional integrity of both the FDA and the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. One must question whether this evolution enhances public health outcomes or merely optimizes litigation efficiency for entities with sufficient capital. The empirical data on savings - while impressive - does not account for the latent costs of prolonged legal uncertainty, delayed access, and the chilling effect on smaller market entrants. The system, in sum, is neither as elegant nor as equitable as its proponents suggest.